On Darkness, Delight, and the Work of Attention

A conversation with Shabnam Piryaei

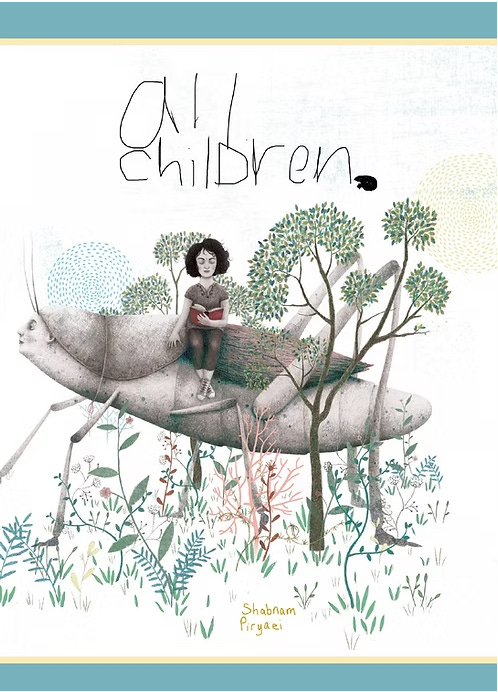

As an editor, there are moments when a manuscript arrives and refuses to stay contained within the usual evaluative frameworks of craft, genre, or market; it insists instead on an ethical and imaginative response. all children. by Shabnam Piryaei was that kind of work for me. From its first pages, the book makes a radical demand: that we hold innocence and brutality together without diluting either, that we allow play, tenderness, and delight to coexist with state violence, neglect, and grief. Its formal daring, borrowing the visual language of children’s magazines, games, and activities, is not a gimmick but a moral strategy, one that draws the reader into participation rather than passive consumption, and asks us to locate ourselves inside what we witness. I was compelled to publish this collection because it trusts readers deeply, trusting our capacity to sit with discomfort, to resist easy resolution, and to remember the child as a site of power rather than sentimentality. In this interview, Piryaei speaks with clarity and generosity about ego, darkness, empathy, and form, and about how poetry can function as a portal rather than a conclusion. What follows is a conversation that mirrors the book itself: expansive, unflinching, and rooted in the belief that attention, honesty, and love are not separate from political responsibility, but central to it.

DIODE: all children. moves fluidly between innocence and brutality, play and devastation. How did you think about holding those tensions together without resolving them, and what does that friction allow the book to say?

Shabnam: The form of all children. might be a sign of my own private experience of the world—I am deeply aware of the violence around me all the time, just as I’m aware of the innocence and beauty of children, of worms, of rocks in water. And for at least the first half of my life, I anguished over this juxtaposition of innocence and brutality. It was physically painful to me. My first book, ode to fragile is an ode to the fragility of humans, in particular in the face of darkness, devastation, cruelty and humiliation. It was so heartbreaking for me to write it, and while it’s a truly beautiful book, it’s also incredibly heavy. As are the three films I made from the material in that book. The aura of pain around those pieces makes it difficult for me to return to them. I think now, my relationship with darkness is more refined, and more aligned with my purpose. And I revel in resilience more. Yes, I’m here to engage with, to draw attention to, and to acknowledge, the darkness in the world. But I’m also here to guide people into their own power, to help them feel delight, and joy, and freedom.

The lack of resolution in the book is a surrender to expansion. I’m trying to avoid the death of a fixed answer. So much of my youth was painted by my ego, by the angry conviction of my position—in my case, a sense of moral superiority. Ego has an almost comical authority. It walks on wobbly legs, but wears a dress of fists. It performs certitude at the site of its biggest questions. There’s a lack of tenderness, a lack of attentiveness, and so much fear in the performance of ego. My biggest evolutionary leaps occurred when I sat down with my ego long enough, gently enough, for it to shed its disguises and reveal myself to me. It wasn’t painless, but there was always freedom on the other side.

Darkness does not want to be ignored, it does not want to be covered up with a beautiful blanket. Darkness does not want to remain darkness.

DIODE: The book borrows the visual and structural language of children’s magazines, games, and activities. What drew you to that form, and how did it shape the emotional or ethical stakes of the work?

Shabnam: When I was writing the book, I was really intentional about infusing it with Light. And I had to ask myself, what makes me feel the most delight? What makes me feel the most free? And at the time, the answer was children. Being around kids, expressing my own kid-side. So the first thing I did was give myself permission to play, even in the midst of stories that are devastating.

I also wanted a format that invited play. I want you to find the animals drawn into the scene of the mother and daughter. I want you to do the word puzzles. I want you to see the rough drawings and feel inspired to make your own art. And I want to nourish you, to offer you love and tenderness and levity as I walk you through the dark.

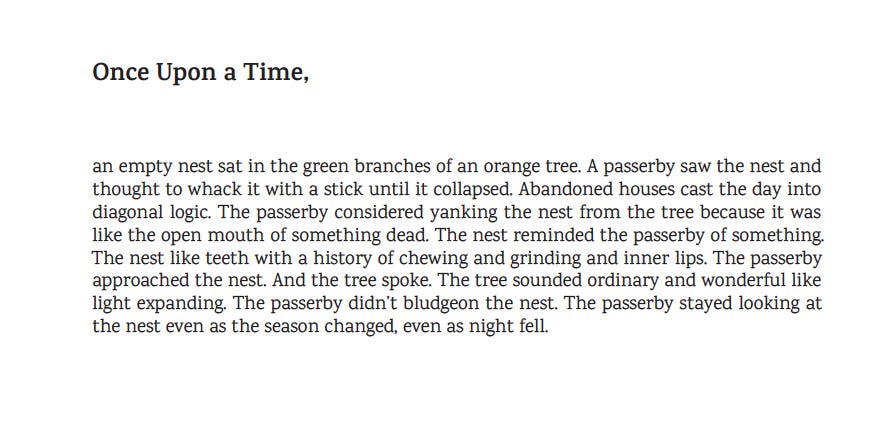

The recurring sections like “Can You Find the Animals in This Picture?” and “Once Upon a Time” feel both familiar and destabilized. How do you see repetition functioning across the book, formally and politically?

Both familiar and destabilized. I like that.

Honesty is integral to how I love. I think it’s beautiful when friends listen and have your back no matter what you say, but that’s not for me. I need everyone around me to be honest with me, even if it’s not easy. I’m not here for short-term gains, I’m here to evolve. And the more I evolve, the more I can creatively, joyfully, and freely offer evolution to others. So the destabilization is related to disrupting illusions that prevent accountability, or repeat harm, or reinforce mythologies of separation.

The familiar part is because I want you to feel safe. I was an only child until I was about 12 and half, and I grew up reading a lot. And a common text was Highlights Magazine, which had repeated segments like Goofus & Gallant, or letters & drawings from readers, or short stories with illustrations, or arts and crafts. And I had a subscription, so I knew the magazine would arrive every month. Another repetition. There was comfort in the repeated structure, and also a wonder and curiosity for the shifting storylines and ideas. So the familiarity in the book is deliberate. I use it as a way to be tender with myself, and as nostalgia for me and readers. It’s a way to build comfort into the dna of the book, while also serving as a portal directly to the child in every reader.

And, honestly, I’m aware of what the dissonance does. The way the more difficult parts of the story are amplified or re-cast in this more child-like setting. But sometimes it’s children who are experiencing it, and I think I found that for this project, this structure conveys the depth of the violence, and its relation to light, in a more faithful way.

The voice in all children. often speaks from multiple positions at once: parent, witness, child, narrator, citizen. How did you navigate voice while writing, and did it shift over time as the book took shape?

Two of my spiritual gifts are that I am an empath, and that I channel. For a long time that meant my feelings were messy and confusing because I didn’t know why I was feeling the way I was. I’ve gotten so much better at discerning what’s mine and what isn’t, including emotion, voice, energy. It’s a benefit because I can really receive and embody people and experiences, and the more I refine my craft of writing, I can communicate those people whole. I can always sabotage the work by overthinking it or trying too hard to control it. But when I really surrender and I’m being discerning, I can co-create with them to make something really beautiful.

DIODE: Several pieces engage real-world events and public language, particularly around state violence and neglect. How did you decide when to incorporate found or journalistic material, and how to transform it poetically?

Shabnam: That’s a great question. I think sometimes I need to point at the world and say, See? Right here? This is what I’m talking about. Look at this one individual person, this one beautiful child, for example, look right at them.

I’m drawing connections between fixed stories about specific people in the news with other people from different times and geographies who share the experience of violence. In the poem Current Events, for example, I’m talking about siblings who were gassed to death in Syria while hiding in a basement, a terrified and crying 10 year old Black boy in Chicago who was handcuffed by adult police in front of his grandmother’s house, migrant children who journeyed all the way to the US/Mexico border only to be forcibly separated from their guardians and sent to abusive shelters, and kids who daily suffer domestic abuse in their own homes.

In Current Events I juxtapose these “real-world” excerpts with poems which are permeable and infinite, even if they’re sad. It’s like planting a portal there. Poems are so special—they can connect anything together, revering the relation between even the most seemingly disparate things. There’s an abundance in this, an inexhaustibility, an infinity that I hope nourishes the reader and feeds the people in the stories I’m sharing.

DIODE: This book resists easy categorization as poetry, prose, or visual work. How do you hope readers move through it, slowly, disruptively, intuitively, or otherwise?

Shabnam: I hope it’s a mirror for the reader. May they feel how expansive and varied they are. May they know that time is not linear. May they remember that everything is connected to everything else. May they nestle in the inquiry. May they bring their inner child to witness their current selves, and may there be reciprocity between them.

Are there particular readings, performances, or conversations around all children. that have surprised you or helped you see the book differently since publication?

I think this is the first time I haven’t shrouded my work in an energy to keep it small after it’s complete. I used to have a tendency to stay hidden to protect myself. But this time, I really let the work lead the way. In other words, it’s not about me or my fears. So I’ve been doing far more readings than I ever have in order to share this book. And, as all children. continues to show me how it wants to be received, it’s helping me embrace, and enjoy, being seen.

DIODE: Looking ahead, what are you working on now, and how does that work converse with or depart from all children.? Are there upcoming events, readings, or projects you would like readers to know about?

The things I’ve written about aren’t “done.” I wrote a poem in 2006 called Beit Hanoun, which is a town in Gaza, and it was published in my first book. And the poem was prompted by the image of a tiny pink upturned shoe in a puddle of blood after Israel had bombed a neighborhood there. In all children., I have a poem called Mad Libs: Sightseeing Iran in Summer. In that piece, I’m describing a scene where men are being executed in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

I’m continuing to write about and create art that considers violence, including state violence.

Right now, I’m working on a collection of personal essays which I am so very excited about. The first essay called The Victory Belongs to Love was published in Hunger Mountain, and the second called my dad has dementia is forthcoming in Blackbird. I also recently finished a documentary film about asylum seekers across the US/Mexico border called No Separate Survival, and we’ve been doing screenings and panel discussions for the film.

I’ll be doing two poetry readings at the San Francisco Public Library in March and April to keep sharing all children. a book which I love so, so much. And I’ve just finished a manuscript based on my PhD dissertation that looks at state violence in the Islamic Republic of Iran and Iranian films as a site of discourse and resistance.

And as always, I’m writing poetry, which will culminate in my next book of poems.

People can learn more about what I do at my personal website.

Everything I’m doing is an aspiration to continue integrating together all aspects of who I am, and to help people feel their own power and remember who they are.

Wow! What exciting work! Can't wait to read!